Editor-at-large Robert Barry summarises the outcome of the lack of a national policy on fleet emissions and looks at future green technology on offer for fleets.

Today New Zealand has no cohesive overall fleet policy or mandate in regards to emissions, with the exception that all new vehicles imported for sale must meet ADR/EU/USA or Japanese domestic compliance standards to enter our market.

Ironically there is some policy governing the national fleet make-up, but it focuses on second hand imports which are now subject to the Japan 2005 emission standard which came into effect earlier this year.

But it didn’t have to be this way because the previous Labour-led government did implement policy on our carbon footprint.

In 2007 it was the intention of the Govt3 fleet policy to reduce the carbon footprint and improve the overall fuel consumption of its entire fleet by five percent through the purchase of diesel and hybrid vehicles, which were fit for purpose and met five-star safety impact requirements.

The policy also encouraged the use of mass transport or non-polluting transports where practical and appropriate. The Labour Government had signed up to the Kyoto agreement and was actively trying to meet the obligations.

The long-term strategy for the government fleet under the Labour regime was carbon zero – an ambitious target.

It was the intention of the Govt3 fleet policy that the diesel and hybrid vehicles would reduce the national carbon footprint when they were sold off at the end of their working life.

In early 2009 the National-led government scrapped Govt3. Meeting Kyoto protocol obligations flew out the window and saving money came in – such is the nature

of politics.

An “all-of-government” tender for vehicles was set up by the Ministry of Economic Development in 2010.

Unfortunately the rationale behind the tender was cost saving – in a nutshell, how cheaply could the Government buy vehicles from the local distributors?

This result was vehicles selected that didn’t necessarily meet the needs of the departments, nor did some options offer the safety or efficiencies of the previous regime.

A minimum of 4-star impact protection rather than 5-star was admissible under the all-of-government tender process.

Some government departments have elected to keep their older cars because the newer all-of-government tender does not provide the choice or the cost-effective options of the Govt3 selection criteria.

How has this affected the private fleet?

It seems the global financial crisis has had more impact on fleet policy than the Government.

By cutting out unnecessary benefit cars and focusing on four-cylinder mid-size and SUV vehicles for use as tool-of-trade vehicles, the make up of NZ fleets has changed considerably since October 2008.

A global focus by the manufacturers on reducing vehicle emissions and improving safety technology since 2008 has enabled fleets today to choose much better-performing vehicles that are still fit for purpose.

Large cars have become more efficient, yet the demand has shrunk considerably, though this trend started well before 2008.

Sales of the Holden Commodore still surprise, although in its home market of Australia it was overtaken by the Mazda3 last year for the number one sales spot.

In Australia the Mazda3 sold 41,429 units in comparison to the 40,617 Commodores sold by Holden.

It is the rising numbers of SUV and medium car sales that show the fleet market trends which are also reflected globally.

In New Zealand post-October 2008 the total SUV market share has increased by 9 percent to 29 percent overall. Despite some SUV models being less than fuel efficient and emissions friendly they offer the best compromise for work and lifestyle choice and continue to sell strongly in the current market.

An electric future? Feasible or fallible?

New Zealand generates more than 70 percent of its electricity from renewable resources, in effect green power.

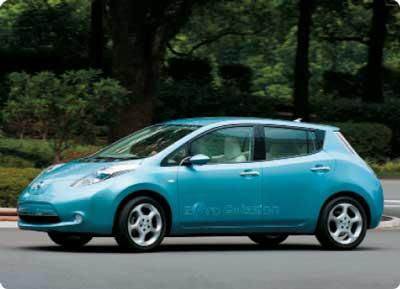

The initial cost of new fully electric vehicles (EV) and plug-in petrol-electric hybrid vehicles (PHEV) is going to be high because we are still in the early adoption stage of this technology.

The retail price for the Mitsubishi i-Miev EV, for example, is just under $60,000, because unlike overseas markets there is no government subsidy to encourage private and fleet buyers into the purchase of these vehicles.

However despite this barrier to adoption there is another alternative, according to Rob McEwen from the Association for the Promotion of Electric Vehicles (Apev).

Apev says there’s nothing in the middle ground for adopters of electric vehicles between an electric scooter retailing for $2,500 and the Mitsubishi i-Miev at around $60,000.

Therefore Apev has decided to embark on a programme to convert small fleets of existing vehicles with internal combustion (IC) engines into full EVs for commercial applications.

It’s a quintessentially Kiwi solution - build it yourself - but Apev has taken a much wider view by gathering all stakeholders together and also implementing a system of standards and procedures to weed out any future risks.

By looking across large fleets owned by councils, local bodies, and health boards to aggregate demand, Apev believes it can deliver a programme to electrify fleet vehicles at a competitive cost through creating a robust infrastructure of component suppliers and vehicle builders throughout New Zealand.

Apev seeks to create economies of scale by working with interested stakeholders who want to electrify their vehicle fleets, and it has also worked with LVVTA (Low Volume Vehicle Technical Association) to create guidelines and a certification procedure for providers of such vehicle conversions.

Apev also has plans to develop an indemnity insurance programme for conversion suppliers and to provide insurance for the purchaser of the EV(s) as well.

“We want to drive down the costs of entry into EVs, but we also wanted to ensure there was a national standard and structure in place to remove any risk of shoddy or unsafe conversion practice,” says Rob McEwen.

“We believe councils and local bodies are a key to the road for electrification in New Zealand and that developing a strategy at a regional level is the best way to drive this forward.”

If you are not familiar with the term ‘range anxiety,’ it refers to the anxiety of the driver of an EV that he or she may run out of battery power before they reach their intended destination.

The majority of new EVs have a range between 100 and 160km of travel, which is supposedly more than enough for most urban commuters. However this range can vary depending on battery type, weather, terrain, and driving style.

Rob McEwen argues that the initial market for EVs are commercial users rather than private consumers, and therefore most will only be undertaking short trips that will be well within the range of the vehicle.

He also feels that because 85 percent of New Zealand homes have an existing garage with a power outlet, the lack of a commercial charging infrastructure is not the barrier here that it is overseas.

EV drivers in NZ can cost-effectively convert the power outlet in their garage to a charging station which can make use of off-peak power generated overnight by renewable resources such as wind and geo-thermal power. Learn more about Apev via its website at www.apev.org.nz

The diesel alternative

Mazda has started production of the Mazda CX-5 with its new-generationSkyActiv petrol and diesel engines which will contribute towards the company’s “Sustainable Zoom-Zoom” vision of a 30 percent improvement in fuel economy and emissions by 2015.

Mazda says the SkyActiv-D 2.2 diesel engine is the first to comply with global exhaust gas regulations, including Japan’s Post New Long-Term Regulations and Europe’s Euro6, without the need for an expensive nitrogen oxide (NOx) after-treatment system, such as the urea selective catalytic reduction (SCR) system or lean NOx trap (LNT) catalyst.

By precisely controlling fuel injection and improving the exhaust valve’s opening and closing mechanism, the Skyactiv-D diesel engine has achieved breakthroughs on long-standing issues encountered in low compression ratio engines such as poor start capability and lower combustion stability when the engine is cold. These improvements helped to achieve a compression ratio of up to 14:1 for a diesel engine for mass production vehicles.

Mazda says its first diesel-powered compact SUV delivers torque equal to a 4-litre V8 but with the emissions and fuel economy of small and light-size passenger cars.

With the introduction of the Mazda CX-5 with the Skyactiv-D turbo diesel engine together with the Skyactiv-Drive 6-speed automatic transmission, Mazda says it is offering an affordable and credible option to the eco-car market.

Changing trends, changing mindsets

As fleet owners and managers, it is your vehicle purchases today that dictate the future fleet and national car park.

If for example, you all decided to boycott vehicles with less than 5-star safety ratings, then a message will be sent loudly and clearly to the local distributors.

By setting your vehicle policies, for example, to exclude vehicles that emit more than 180gm/km of C02, and again, for example, have an average fuel consumption of less than 9L/100km, then you will actively improve our vehicle carpark as well as your bottom line and carbon footprint.

In the absence of any national policy set by government, it is the fleet market that drives our new car sales and effectively governs what the national

carpark will look like in years to come.

Therefore, as buyers or leasees of fleet vehicles, you have the ability and financial clout to continue to change the trends and change the mindset when it comes to the national fleet.